The temperature was freezing, but the view was spectacular. The snow-clad lofty peaks of Mount Kanchenjungha spread across the horizon in the distance. However, neither the cold nor the jaw-dropping views distracted the team of researchers from the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS). They had gathered in a small shack at the Thambi View Point in eastern Sikkim. It was a roadside viewpoint at an altitude of over 3,400 m along the treacherous, zig-zagging mountain route from Zuluk to Gnathang Valley, with several deadly hairpin bends. They were pouring over a laptop with a memory card from a camera trap inserted in it. One after the other, the images captured by the camera trap flashed before their eyes.

Images of Himalayan gorals appeared several times, and the endangered Himalayan musk deer was also seen. There was even a golden cat, an incredibly elusive and rarely seen species. However, the researchers were expecting something more. There were over 500 images, and going through each and every image was arduous, but they must do it. And then, all of a sudden, there it was – a striped tail of a tiger in one image and the full tiger in the next one.

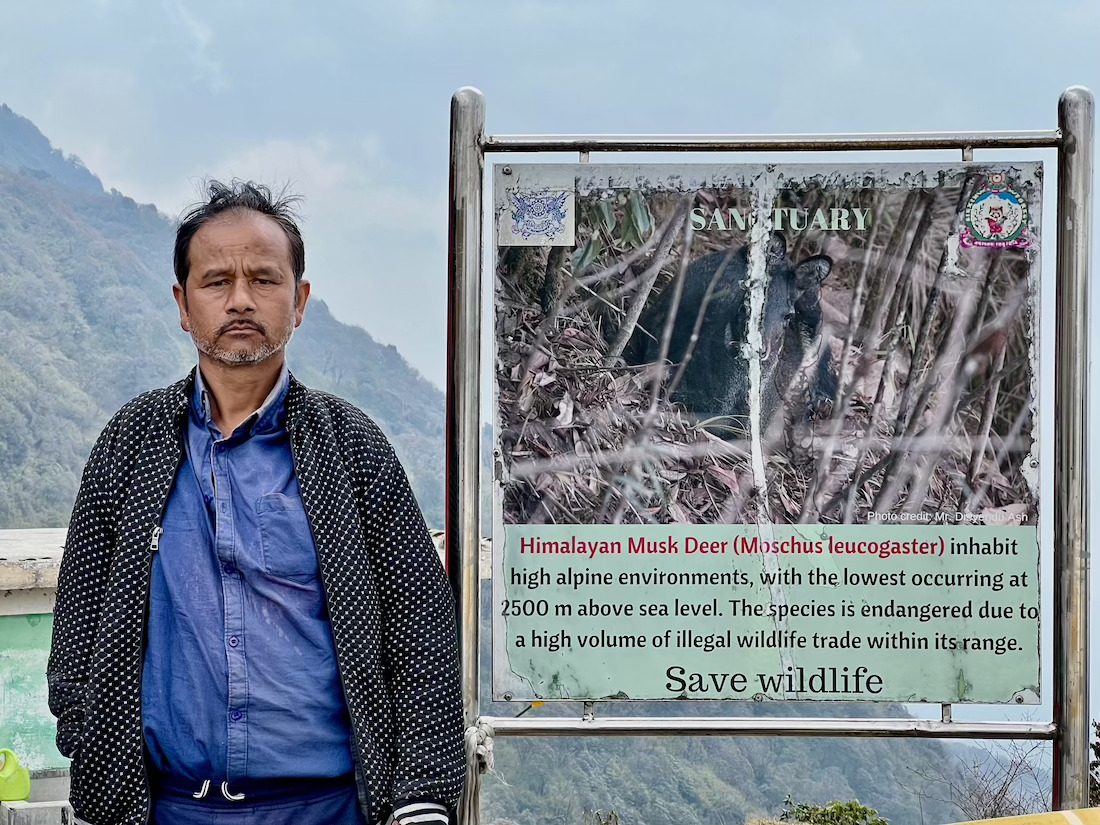

“When we reported this tiger’s presence in Sikkim’s Pangolakha Wildlife Sanctuary in December 2023 at an elevation of 3,640 m, it was the highest camera trap captured record of a tiger in India at that time. Our hard work and good luck worked in unison to gift us this sighting,” said Atharva Singh, BNHS scientist working in eastern Sikkim.

The news of the tiger at 3,640 m was widely shared. It once more opened up conversation on tigers recorded at high altitudes and what it meant for their conservation and the ecosystem as a whole.

Historic Records Of High-Altitude Tigers

The earliest record of a tiger in Sikkim’s mountains goes back to 1924, in colonial India. British intelligence officer F. M. Bailey was chasing a tiger in a quest to hunt it down and traced the animal to the high altitude ranges of Sikkim at an elevation of over 4,000 m.

Several anecdotal references to sightings of tigers or signs of their presence also exist. For example, a middle-aged Krishna Sharma, an eco-development committee member from Zuluk in Sikkim, mentions hearing tales of tiger sightings in his younger days in the forests around Zuluk, a quaint little hamlet bordering the Pangolakha Wildlife Sanctuary at an elevation of 2,900 m.

“I had seen tiger pawprints in the forested mountains near Zuluk in my younger days. We used to, however, still go to the forests to collect wood and were not worried about the tiger’s presence. There were also reports of fellow villagers seeing tigers crossing over our bridges towards Bhutan,” said Sharma.

In recent times, as tiger conservation activities have picked up pace in India, technologies like camera trap photography have made it easier to detect tigers in the remote and challenging terrains of the Himalayas by various organisations.

In 2019, camera traps captured two tigers in northern Sikkim at elevations of 2,425 m and 3,602 m.

Outside Sikkim, high-altitude tigers have also been detected in other Himalayan states. In 2017, these big cats were recorded in the Dibang Valley of Arunachal Pradesh at 3,246 m and 3,630 m. There are also several records of tigers from the Himalayas in Uttarakhand, including a 2019 documentation of a tiger at 3,431 m in the Kedarnath Musk Deer Sanctuary.

In neighbouring Bhutan, where tiger surveys in mountainous landscapes are much more extensively conducted, multiple records of tigers at high elevations exist, with the country reporting the world’s highest altitude tiger at above 4,000 m. Tigresses with cubs have also been found in Bhutan at elevations of around 2,500 m, implying that tigers do breed in mountainous landscapes.

The BNHS Finding

The BNHS team’s recent finding of a tiger at 3,640 m happened during a biodiversity survey in Sikkim, which was part of a research project funded by the National Mission on Himalayan Studies. The team had installed camera traps in their study area in the Pangolakha Wildlife Sanctuary based on previous sightings of pugmarks and scat of what they thought could be that of a tiger in the area. The camera traps were allowed to stay for a couple of months before they were extracted and studied. Chances were low, given the extreme rarity of such sightings. However, luck struck, and they had the tiger captured in the camera trap.

The place where the tiger was found was an ecotone, a transition zone where the tree line gave way to alpine meadows. The camera traps installed in the area also detected the presence of various other species in the area.

These included tiger prey species like the Himalayan goral, Himalayan musk deer, and free-ranging yaks. Himalayan black bear, Himalayan red fox, yellow-throated marten, and even the much-adored red panda were also found. Birds of note included the Himalayan monal and the Satyr tragopan.

Significance Of The Findings

We generally picture tigers as living in lowland forests and grasslands and think of the mountains as home to species like the snow leopard. However, evidence of tigers’ presence in the mountains has shown us that nothing is out of limits for this highly resilient species.

“If a good prey population and undisturbed habitat is present, there is a high probability that the high mountains, like the upper ranges of the Pangolakha Wildlife Sanctuary in Sikkim, can serve as suitable habitat to the tiger, considering they are already doing so in Arunachal Pradesh and Bhutan,” said Atharva.

Indeed, tigers are found in a wide variety of habitats, from frigid Siberia to the hot tropical forests of Southeast Asia to the swampy mangroves of Sundarbans.

Experts believe that more research is needed to come to any conclusion regarding the high-altitude tigers of India. Some populations, like those in the mountains of Arunachal Pradesh, are known to be residents, but tigers in other areas could be seasonal migrants.

In Sikkim’s Pangolakha, the tigers could be migrants from the adjacent Neora Valley Wildlife Sanctuary of West Bengal or the forests of Bhutan. However, if the conditions are suitable, there is no barrier to tigers becoming residents there.

While historical records and anecdotal references have indicated that tigers have always been present in the Himalayas, several reasons can be attributed to the recent rise in tiger sightings in the region.

According to experts, it could be better technology like camera traps and more exploratory research methodologies that have helped generate more evidence of the tiger’s presence in the high mountains. It could also be the rise in tiger populations in and around the protected areas in the lower altitudes that has forced tigers to migrate out in search of newer territory.

Another factor that has often been discussed is the role of climate change in creating more high-altitude-dwelling tigers.

“Right now, we cannot link the presence of tigers in high altitudes to climate change as we do not have enough data to prove the same. We need to conduct long-term monitoring studies in the landscape to investigate the role of climate change on altitudinal variation in tiger habitat,” stated Atharva.

Thus, while many questions remain unanswered regarding the high-altitude tigers of India, these big cats appear to be gaining new heights. Following the BNHS report of a tiger at 3,640 m, the Wildlife Institute of India, in collaboration with the Sikkim forest department, published their study showing the presence of a tiger at 3,966 m at the Kyongnosla Wildlife Sanctuary of Sikkim, making it the highest tiger sighting in India as of now.

In the end, we can say one thing for sure: every time this majestic predator claims a higher elevation, it leaves us in awe of its grand presence in the lofty Himalayas, making us wish that one day we could see this striped beauty with our own eyes against the jaw-dropping backdrop of the lofty Himalayan peaks.